SHANGANI PATROL (1970)

Directed by David Millin

Produced by Roscoe Behrmann

Screenplay by Adrian Steed

Story "A Time to Die" by Robert Cary (1968)

Based on historical events of the Shangani Patrol (1893)

Starring Brian O'Shaughnessy as Maj. Allan Wilson

Will Hutchins as Chief of Scouts Frederick Russell Burnham

Music by Mike Hankinson and Dan Hill

RPM Studio Orchestra

Cinematography - Lionel Friedberg

Edited by Antony Gibbs

Production Company - RPM Film Studios

Distributed by Rhodesian Broadcasting Corporation

Release Date - 3 December 1970

Running Time - 90 min.

Country - Rhodesia

Language - English

Shangani Patrol is a South African film made by RPM in 1970.

Shangani Patrol is a war film based upon the non-fiction book A Time to Die by Robert Cary (1968), and the historical accounts of the Shangani Patrol, with Brian O'Shaughnessy as Major Allan Wilson and Will Hutchins as the lead Scout Frederick Russell Burnham. Also includes the song "Shangani Patrol" by Nick Taylor (1966 recording).

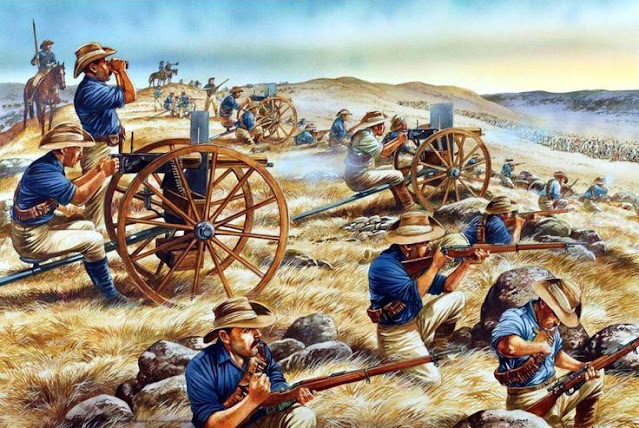

Under the command of Major Wilson, the patrol tracks the fleeing Ndebele King Lobengula across the Shangani River. Cut off from the main force, they are ambushed by the Ndebele impi and, except for the few men sent as reinforcements, all are killed. Such was the bravery of the Shangani Patrol that the victorious Ndebele said, "They were men of men and their fathers were men before them." Depending on one's viewpoint, this event was one of the great mistakes and military blunders of this time in history or the last heroic stand of a gallant few. The incident had lasting significance in England, South Africa, and Rhodesia as the equivalent of 'Custer's Last Stand'. This is their story, told in a 1970 film shot on location in Matabeleland, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).

==================================================================================================================================================

PLOT

Locale, Mashonaland, Southern Rhodesia, 1893. The British South Africa Company (BSAC) (later to become the British South African Police - BSAP) is based in the encampment of Fort Salisbury (now the capital of Zimbabwe, Harare). The film starts with a sepia toned trial of two AWOL volunteers and later deserters who were eventually court martialed by the army for stealing gold which was given to them by Matabele warriors on behalf of King Lobengula as a peace offering to end the war. In this trial (which is solely represented by archive drawings and voice-overs) the voice of TV anchor man/journalist Adrian Steed is heard as the judge (later to be seen as Major Forbes) and that of Stuart Brown playing Dr Leander Starr Jameson.

The film then cuts to a glorious sunset shot of Southern Rhodesia where the camp is situated. After a sentimental encounter between the leader Allan Wilson and his soon to be wife May, in which Wilson professes the fervent wish to procreate with his wife in order to produce pioneer Rhodesians, it cuts to the titles of the film, all based on scenes from the film. The horrific and ultimately unavoidable slaughter of the Patrol is included. Fort Salisbury has a serious problem; it is surrounded by hordes of menacing Matabele warriors, one of whom demands the release of the Shona people under the protection of the BSAC and promises that his warriors will kill them in the bush and not in the Shangani River so as not to dirty the water.

The BSAC re-group and under orders from Dr. Jameson, are to pursue King Lobengula’s troops all the way down from Fort Salisbury to the south of Rhodesia, at that time the kingdom of Lobengula, to capture King Lobengula and hold him to ransom.

Wilson leads his troops on what has become a heroic but ultimately futile quest to capture the King in the hope that his troops will surrender. One by one, the volunteers begin showing signs of their inexperience and sometimes lack of courage. One even loses his nerve, runs away and is shot while fleeing.

Eventually, with ammunition and morale running low, Wilson dispatches Burnham back to the fort to alert Major Forbes that reinforcements are required. After much argument, Burnham complies and the Shangani Patrol is minus another volunteer.

Burnham alerts Major Forbes to the peril that the Patrol is in. Forbes refuses to back his troops up.

The Patrol is eliminated by the Ndebele after Wilson fires his remaining bullet. He and the party are killed by the Matabele, who then praise the 34 men of the Shangani Patrol as being "men of men".

The final slaughter of the vanquished is shown in quick fire frame flashes (almost like still pictures) and with no sound, right up until the moment when the Matabele induna screams "Touch not their bodies! They were men of men and their fathers were men before them!" The last scene is of Burnham visiting the burial and monument to the Shangani Patrol at Matopo Hills.

==================================================================================================================================================

PRIMARY CAST

Brian O'Shaughnessy

|

| Major Allan Wilson |

Will Hutchins

Will Hutchins (born Marshall Lowell Hutchason; May 5, 1930) is an American actor most noted for playing the lead role of the young lawyer Tom Brewster, in the Western television series Sugarfoot, which aired on ABC from 1957 to 1961 for sixty-nine episodes.

|

| Frederick Russell Burnham |

Adrian Steed

Adrian Steed was born in the UK on 3rd June 1934, he arrived in South Africa in 1956 and had a busy career in Radio, Film and TV until 1996. He works as a media advisor.

|

| Major Patrick Forbes |

Stuart Brown

|

| Dr. Leander Starr Jameson |

Anthea Crosse

Born in 1938, Lambeth London, Anthea graduated from RADA in 1957.

|

| May Thompson |

Pieter Hauptfleisch

South African Actor. He was born in Bloemfontein. Died 1973

|

| Captain |

Don McCorkindale

British Actor, Born in London in 1939

|

| Forbes' ADC |

Patrick Mynhardt

South African Actor. Died London 2007.

|

| Lieutenant Hofmeyr |

Dale Cutts

South African Actor. Dale was born in Durban in 1939 and attended the Northlands Boys High School. He was married to Janine Neethling. Dale Cutts died in South Africa on April 19, 2013

|

| Captain Henry John Borrow |

George Jackson

|

| Trooper James Wilson |

Ralph Loubser

|

| Trooper William Daniel |

Robin Dolton

|

| Sgt. Harold Brown |

Victor Mackeson

|

| Trooper Jack Robertson |

Peter Jackson

|

| Captain Argent Kirton |

Ian Hamilton

|

| Captain William Judd |

FULL CAST

Brian O'Shaughnessy ... Maj. Allan Wilson

Will Hutchins ... Frederick Russell Burnham

Adrian Steed ... Maj. Patrick Forbes

James White ... Trooper

Patrick Mynhardt ... Lt. Arend Hofmeyr

Anthea Crosse ... May Thompson

Ian Yule ... Trooper Dillon

Pieter Hauptfleisch ... Captain

Ian Hamilton ... Capt. William Judd

Stuart Brown ... Dr. Leander Starr Jameson

Victor Mackeson ... Trooper Jack Robertson

Robin Dolton ... Sgt. Brown

Don McCorkindale ... Forbes' A.D.C.

Lance Lockhart-Ross ... Capt. William Napier

Roland Robinson ... Capt. Fred Fitzgerald

Wilson Dunster ... Trooper Henry

Dale Cutts ... Capt. Henry Borrow

Fred de Wet ... Trooper

Ken Leach ... Trooper

Peter Jackson ... Captain

Ralph Loubser ... Trooper William Daniel

George Jackson ... Trooper James Wilson

Wilson Mphofu ... Matabele Chief

Production

Shangani Patrol was the third film made by South African producers David Millin and Roscoe Behrmann under the newly formed RPM Film Studios. The film was shot entirely on location in Rhodesia, in the Marula district, about sixty miles from Bulawayo and not far from the historical battles of the First Matabele War. Shooting was completed in the scheduled six weeks.

=================================================================================================================================================

THE SHANGANI PATROL

|

| Wilson's Last Stand |

|

| King Lobengula and one of his wives. |

BACKGROUND

|

| British South African Company Column. |

PRELUDE: FORBES'S PURSUIT OF LOBENGULA

ENGAGEMENT

MATABELE AMBUSHES ON BOTH SIDES OF THE RIVER

WILSON'S LAST STAND

AFTERMATH

CULTURAL IMPACT, BURIAL & MEMORIAL

CONTROVERSY

LOBENGULAS'S BOX OF SOVEREIGNS

BURNHAM, INGRAM & GOODING

LEGACY

MEN OF THE SHANGANI PATROL

THE FALLEN

WITNESS STATEMENT

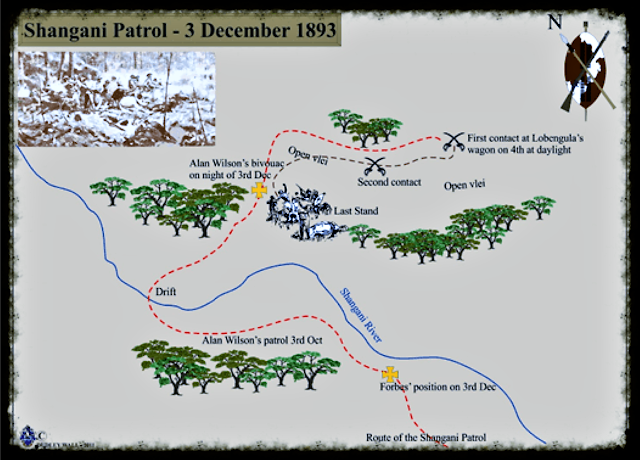

by Frederick Russell Burnham

In the afternoon of December 3, I was scouting ahead of the column with Colenbrander, when in a strip of bush we lit on two Matabele boys driving some cattle, one of whom we caught and brought in. He was a plucky boy, and when threatened he just looked us sullenly in the face. He turned out to be a sort of grandson or grand-nephew of Lobengula himself. He said the King's camp was just ahead, and the King himself near, with very few men, and these sick, and that he wanted to give himself up. He represented that the King had been back to this place that very day to get help because his wagons were stuck in a bog.

The column pushed on through the strip of bush, and there, near by, was the King's camp—quite deserted. We searched the huts, and in one lay a Maholi slave-boy, fast asleep. (The Maholis are the slaves of the Matabele.) We pulled him out, and were questioning him, when the other boy, the sulky Matabele caught his eye, and gave him a ferocious look, shouting across to him to take care what he told

The slave-boy agreed with the others that the King had only left this camp the day before; but as it was getting dark, Major Forbes decided to reconnoitre before going on with the column. I learnt of the decision to send forward Major Wilson and fifteen men on the best horses when I got my orders to accompany them, and, along with Bayne, to do their scouting. My horse was exhausted with the work he had done already; I told Major Forbes, and he at once gave me his. It was a young horse, rather skittish, but strong and fairly fresh by comparison.

Ingram, my fellow-scout, remained with the column, and so got some hours' rest; thanks to which he was able not only to do his part of tracking for the twenty men afterwards sent on to us through the bush at night, but also, when he and I got through after the smash, to do the long and dangerous ride down country to Bulawayo with the dispatches—a ride on which he was accompanied by Lynch.

So we set off along the wagon track, while the main body of the column went into laager. Close to the river the track turned and led downstream along the west bank. Two miles down was a drift' (they call a fordable dip a drift in South Africa), ' and here the track crossed the Shangani. We splashed through, and the first thing we scouts knew on the other side was that we were riding into the middle of a lot of Matabele among some scherms, or temporary shelters. There were men, and some women and children. The men were armed. We put a bold face on it, and gave out the usual announcement that we did not want to kill anybody, but must have the King.

The natives seemed surprised and undecided; presently, as Major Wilson and the rest of the patrol joined us, one of them volunteered to come along with us and guide us to the King. He was only just ahead, the man said. How many men were with him? we asked. The man put up his little finger—dividing it up, so. Five fingers mean an impi; part of the little finger, like that, should mean fifty to one hundred men. Wilson said to me, "Go on ahead, taking that man beside your saddle; cover him, fire if necessary, but don't you let him slip."

So we started off again at a trot, for the light was failing, the man running beside my horse, and I keeping a sharp eye on him. The track led through some thick bush. We passed several scherms. Five miles from the river we came to a long narrow vlei [a vlei is a shallow valley, generally with water in it], which lay across our path. It was now getting quite dark.

Coming out of the bush on the near edge of the vlei, before going down into it, I saw fires lit, and scherms and figures showing dark against the fires right along the opposite edge of the vlei. We skirted the vlei to our left, got round the end of it, and at once rode through a lot of scherms containing hundreds of people. As we went, Captain Napier shouted the message about the King wherever there was a big group of people. We passed scherm after scherm, and still more Matabele, more fires, and on we rode.

Instead of the natives having been scattering from the King, they had been gathering. But it was too late to turn. We were hard upon our prize, and it was understood among the Wilson patrol that they were going to bring the King in if man could do it. The natives were astonished: they thought the whole column was on them: men jumped up, and ran hither and thither, rifle in hand. We went on without stopping, and as we passed more and more men came running after us. Some of them were crowding on the rearmost men, so Wilson told off three fellows to "keep those niggers back." They turned, and kept the people in check. At last, nearly at the other end of the vlei, having passed five sets of scherms, we came upon what seemed to be the King's wagons, standing in a kind of enclosure, with a saddled white horse tethered by it. Just before this, in the crowd and hurry, my man slipped away, and I had to report to Wilson that I had lost him. Of course it would not have done to fire. One shot would have been the match in the powder magazine. We had ridden into the middle of the Matabele nation.

At this enclosure we halted and sang out again, making a special appeal to the King and those about him. No answer came. All was silence. A few drops of rain fell. Then it lightened, and by the flashes we could just see men getting ready to fire on us, and Napier shouted to Wilson, "Major, they are about to attack."

I at the same time saw them closing in on us rapidly from the right. The next thing to this fifth scherm was some thick bush; the order was given to get into that, and in a moment we were out of sight there. One minute after hearing us shout, the natives with the wagons must have been unable to see a sign of us. Just then it came on to rain heavily; the sky, already cloudy, got black as ink ; the night fell so dark that you could not see your hand before you.

We could not stay the night where we were, for we were so close that they would hear our horses' bits. So it was decided to work down into the vlei, creep along close to the other edge of it to the end we first came round, farthest from the King's camp, and there spend the night. This, like all the other moves, was taken after consultation with the officers, several of whom were experienced Kaffir campaigners. It was rough going; we were unable to see our way, now splashing through the little dongas that ran down into the belly of the vlei, now working round them, through bush and soft bottoms. At the far end, in a clump of thick bush, we dismounted, and Wilson sent off Captain Napier, with a man of his called Robinson, and the Victoria scout, Bayne, to go back along the wagon-track to the column, report how things stood, and bring the column on, with the Maxims, as sharp as possible. Wilson told Captain Napier to tell Forbes if the bush bothered the Maxim carriages to abandon them and put the guns on horses, but to bring the Maxims without fail. We all understood—and we thought the message was this—that if we were caught there at dawn without the Maxims we were done for. On the other hand was the chance of capturing the King and ending the campaign at a stroke.

The spot we had selected to stop in until the arrival of Forbes was a clump of heavy bush not far from the King's spoor—and yet so far from the Kaffir camps that they could not hear us if we kept quiet. We dismounted, and on counting it was found that three of the men were missing. They were Hofmeyer, Bradburn and Colquhoun. Somewhere in winding through the bush from the King's wagons to our present position these men were lost. Not a difficult thing, for we only spoke in whispers, and, save for the occasional click of a horse's hoof, we could pass within ten feet of each other and not be aware of it.

Wilson came to me and said, "Burnham, can you follow back along the vlei where we've just come?" I doubted it very much as it was black and raining; I had no coat, having been sent after the patrol immediately I came in from firing the King's huts, and although it was December, or midsummer south of the line, the rain chilled my fingers. Wilson said, " Come, I must have those men back." I told him I should need some one to lead my horse so as to feel the tracks made in the ground by our horses. He replied, "I will go with you. I want to see how you American fellows work."

Wilson was no bad hand at tracking himself, and I was put on my mettle at once. We began, and I was flurried at first, and did not seem to get on to it somehow ; but in a few minutes I picked up the spoor and hung to it. So we started off together, Wilson and I, in the dark. It was hard work, for one could see nothing; one had to feel for the traces with one's fingers. Creeping along, at last we stood close to the wagons, where the patrol had first retreated into the bush.

”If we only had the force here now," said Wilson, "we would soon finish."

But there was still no sign of the three men, so there was nothing for it but to shout. Retreating into the vlei in front of the King's camp, we stood calling and cooeying for them, long and low at first, then louder. Of course there was a great stir along the lines of the native scherms, for they did not know what to make of it. We heard afterwards that the natives were greatly alarmed as the white men seemed to be everywhere at once, and the indunas went about quieting the men, and saying " Do you think the white men are on you, children? Don't you know a wolf’s howl when you hear it?"

After calling for a bit, we heard an answering call away down the vlei, and the darkness favouring us, the lost men soon came up and we arrived at the clump of bushes where the patrol was stationed. We all lay down in the mud to rest, for we were tired out. It had left off raining, but it was a miserable night, and the hungry horses had been under saddle, some of them twenty hours, and were quite done. So we waited for the column.

During the night we could hear natives moving across into the bush which lay between us and the river. We heard the branches as they pushed through. After a while Wilson asked me if I could go a little way around our position and find out what the Kaffirs were doing. I always think he heard something, but he did not say so. I slipped out and on our right heard the swirl of boughs and the splash of feet. Circling round for a little time I came on more Kaffirs. I got so close to them I could touch them as they passed, but it was impossible to say how many there were, it was so dark. This I reported to Wilson. Raising his head on his hand he asked me a few questions, and made the remark that if the column failed to come up before daylight, "we are in a hard hole,” and told me to go out on the King's spoor and watch for Forbes, so that by no possibility should he pass us in the darkness.

It was now, I should judge, 1 A.M. on the 4th of December. I went, and for a long, long time I heard only the dropping of the rain from the leaves and now and then a dog barking in the scherms, but at last, just as it got grey in the east, I heard a noise, and placing my ear close to the ground, made it out to be the tramp of horses. I ran back to Wilson and said "The column is here."

We all led our horses out to the King's spoor. I saw the form of a man tracking. It was Ingram. I gave him a low whistle; he came up, and behind him rode—not the column, not the Maxims, but just twenty men under Captain Borrow. It was a terrible moment—" If we were caught there at dawn "—and already it was getting lighter every minute.

One of us asked "Where is the column?" to which the reply- was, "You see all there are of us." We answered, "Then you are only so many more men to die."

Wilson went aside with Borrow, and there was earnest talk for a few moments. Presently all the officers' horses' heads were together; and Captain Judd said in my hearing, "Well, this is the end." And Kurten said quite quietly, "We shall never get out of this."

Then Wilson put it to the officers whether we should try and break through the impis which were now forming up between us and the river, or whether we would go for the King and sell our lives in trying to get hold of him. The final decision was for this latter.

So we set off and walked along the vlei back to the King's wagons. It was quite light now and they saw us from the scherms all the way, but they just looked at us and we at them, and so we went along. We walked because the horses hadn't a canter in them, and there was no hurry anyway.

At the wagons we halted and shouted out again about not wanting to kill anyone. There was a pause, and then came shouts and a volley. Afterwards it was said that somebody answered, "If you don't want to kill, we do." My horse jumped away to the right at the volley, and took me almost into the arms of some natives who came running from that side. A big induna blazed at me, missed me, and then fumbled at his belt for another cartridge. It was not a proper bandolier he had on, and I saw him trying to pluck out the cartridge instead of easing it up from below with his finger. As I got my horse steady and threw my rifle down to cover him, he suddenly let the cartridge be and lifted an assegai. Waiting to make sure of my aim, just as his arm was poised I fired and hit him in the chest; he dropped. All happened in a moment. Then we retreated. Seeing two horses down, Wilson shouted to somebody to cut off the saddle pockets which carried extra ammunition.

Ingram picked up one of the dismounted men behind him, Captain Fitzgerald the other. The most ammunition anyone had, by the way, was a hundred and ten rounds. There was some very stiff fighting for a few minutes, the natives having the best of the position; indeed they might have wiped us out but for their stupid habit of firing on the run, as they charged. Wilson ordered us to retire down the vlei; some hundred yards further on we came to an ant-heap and took our second position on that, and held it for some time.

Wilson jumped on the top of the ant-heap and shouted—"Every man pick his nigger." There was no random firing, I would be covering a man when he dropped to somebody's rifle, and I had to choose another.

Now we had the best of the position. The Matabele came on furiously down the open. Soon we were firing at two hundred yards and less; and the turned-up shields began to lie pretty thick over the ground. It got too hot for them; they broke and took cover in the bush. We fired about twenty rounds per man at this ant-heap. Then the position was flanked by heavy reinforcements from among the timbers; several more horses were knocked out and we had to quit. We retreated in close order into the bush on the opposite side of the vlei—the other side from the scherms. We went slowly on account of the disabled men and horses.

There was a lull, and Wilson rode up to me and asked if I thought I could rush through to the main column. A scout on a good horse might succeed, of course, where the patrol as a whole would not stand a chance. It was a forlorn hope, but I thought it was only a question of here or there, and I said I'd try, asking for a man to be sent with me. A man called Gooding said he was willing to come, and I picked Ingram also because we had been through many adventures together, and I thought we might as well see this last one through together.

So we started, and we had not gone five hundred yards when we came upon the horn of an impi closing in from the river. We saw the leading men, and they saw us and fired. As they did so I curved my horse sharp to the left, and shouting to the others, “Now for it!" we thrust the horses through the bush at their best pace. A bullet whizzed past my eye, and leaves, cut by the firing, pattered down on us; but as usual the natives fired too high.

So we rode along, seeing men, and being fired at continually, but outstripping the enemy. The peculiar chant of an advancing impi, like a long, monotonous baying or growling, was loud in our ears, together with the noise they make drumming on their hide shields with the assegai—you must hear an army making those sounds to realise them. As soon as we got where the bush was thinner, we shook off the niggers who were pressing us, and, coining to a bit of hard ground, we turned on our tracks and hid in some thick bush. We did this more than once and stood quiet, listening to the noise they made beating about for us on all sides. Of course we knew that scores of them must have run gradually back upon the river to cut us off, so we doubled and waited, getting so near again to the patrol that once during the firing which we heard thickening back there, the spent bullets pattered around us. Those waiting moments were bad. We heard firing soon from the other side of the river too, and didn't know but that the column was being wiped out as well as the patrol.

At last, after no end of doubling and hiding and riding in a triple loop, and making use of every device known to a scout for destroying a spoor—it took us about three hours and a half to cover as many miles—we reached the river, and found it a yellow flood two hundred yards broad. In the way African rivers have, the stream, four feet across last night, had risen from the rain. We did not think our horses could swim it, utterly tired as they now were; but we were just playing the game through, so we decided to try. With their heads and ours barely above the water, swimming and drifting, we got across and crawled out on the other side. Then for the first time, I remember, the idea struck me that we might come through it after all, and with that the desire of life came passionately back upon me.

We topped the bank, and there, five hundred yards in front to the left, stood several hundred Matabele! They stared at us in utter surprise, wondering, I suppose, if we were the advance guard of some entirely new reinforcement. In desperation we walked our horses quietly along in front of them, paying no attention to them. We had gone some distance like this, and nobody followed behind, till at last one man took a shot at us; and with that a lot more of them began to blaze away. Almost at the same moment Ingram caught sight of horses only four or five hundred yards distant; so the column still existed—and there it was. We took the last gallop out of our horses then, and —well, in a few minutes I was falling out of the saddle, and saying to Forbes: "It's all over; we are the last of that party!" Forbes only said, "Well, tell nobody else till we are through with our own fight," and next minute we were just firing away along with the others, helping to beat off the attack on the column.

Shangani Patrol (Soundtrack Album)

Shangani Patrol is the soundtrack to the 1970 film Shangani Patrol. It was released in 1970 and was performed by the RPM Studio Orchestra, composed and conducted by Mike Hankinson, and recorded in RPM Studios Johannesburg, South Africa, by Geoff Tucker. Conducted by the composer Michael Hankinson with a session orchestra. A notable member of this group of musicians was trumpeter Eddie Calvert - also known in England as "The man with the golden horn". Part of the proceeds from the sale of this album were donated to Brandwag Fund/Fond comforts for border troops. The film was based on the true story of the Shangani Patrol.

Track listing

- "Overture" - 2:00

- "Title Music" (Shangani Patrol theme music) by Dan Hill and Mike Hankinson - 3:28

- "Matopos" - 0:42

- "Boarder Battle" - 1:20

- "Poem" - 1:13

- "Leaving Fort Victoria" - 1:09

- "Ringing Rocks" - 1:38

- "Under Attack" - 2:28

- "Jameson's Arrival" - 0:54

- "Diary" - 2:00

- "Stampede" - 1:51

- "Ambush and Escape" - 2:13

- "Call for Reinforcements" - 2:00

- "Night Watch" - 1:20

- "Royal Spear (Matabele Chant)" - 1:30

- "Last Stand" - 2:00

- "To Brave Men" - 0:57

Major Wilson's Last Stand

(1899 Film)

Major Wilson's Last Stand is an 1899 British silent short war film based upon the historical accounts of the Shangani Patrol. The film was adapted from Savage South Africa, a stage show depicting scenes from both the First Matabele War and the Second Matabele War which opened at the Empress Theatre, Earls Courte, on 8 May 1899. It was taken on the field by Joseph Rosenthal for the Warwick Trading Co., Ltd. Copies of this short film originally sold for £3.

The film was shown to audiences at the Olympic Theatre in London and at the Refined Concert Company in New Zealand.

Story

The studio's original description is as follows:

"Major Wilson and his brave men are seen in laager in order to snatch a brief rest after a long forced march. They are suddenly awakened by the shouts of the savages, who surround them on all sides. The expected reinforcements alas arrived too late. The Major calls upon his men to show the enemy how a handful of British soldiers can play a losing game as well as a winning one. He bids them to stand shoulder to shoulder, and fight and die for their Queen. The horses are seen to fall, and from the rampart of dead horses, the heroic band fight to the last round of revolver ammunition. The Major, who is the last to fall, crawls to the top of the head of dead men, savages and horses, and makes every one of the few remaining cartridges find its mark until his life is cut short by the thrust of an assegai in the hands of a savage, who attacks him from behind. Before he falls however, he fires his last bullet into the fleeing carcass of the savage, who drops dead. The Major also expires, and death like silence prevails. The most awe-inspiring cinematograph picture ever produced."

Cast

Texas Jack as Frederick Russell Burnham, the American Chief of Scouts

Peter Lobengula (the son of the real-life Matabele King) as King Lobengula

Francis "Frank" Edward Fillis as Major Allan Wilson

Cecil William Coleman as Captain Greenless

Ndebele warriors—played by Zulu predominantly from the Colony of Natal.

|

| DVD Shangani Patrol |